Medical Dosages

Giving medicine in the right way can help your child feel better and get well faster. However, any kind of medicine can cause harm to a child if given the wrong way. Below will go into the dosage recommendations for a variety of medications.

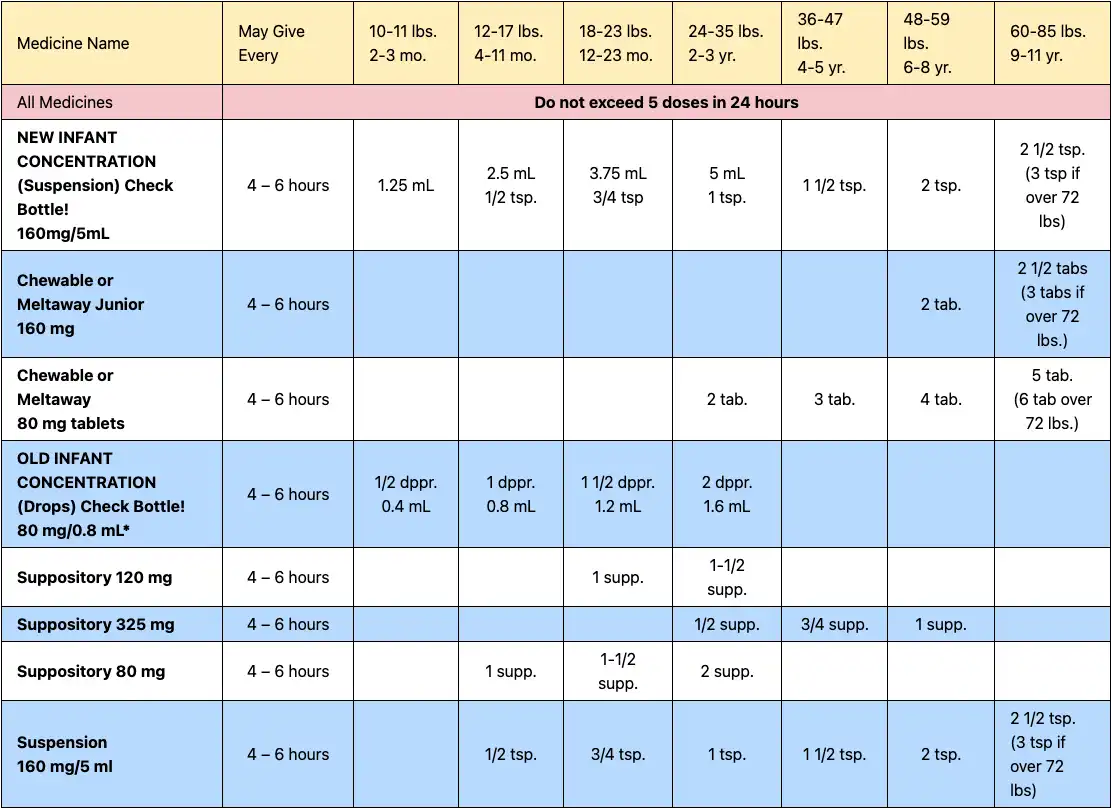

NOTE: New Concentration for Infants. In accordance with FDA recommendations, acetaminophen manufacturers have changed the concentration of infant acetaminophen from 80mg/0.8ml to 160mg/5ml. Be aware that there may be both the old and new concentrations of infants’ acetaminophen products available in stores and in medicine cabinets. The pediatric acetaminophen products currently on the market can continue to be used as labeled. Be sure to check the label or contact our office should you have questions. More Information

Dosages for Acetaminophen medicines for different weights and ages

Getting preschoolers and school-age children to take medicine can be very challenging for parents. Try this: pour the medicine into a small medicine cup, measuring out the exact amount prescribed by your doctor. Then, “top it off” with several teaspoons of either strawberry or chocolate syrup. You also can try this for medicine in tablet form. First, using two spoons, crush the pill into a fine powder. Then, put the powder into the medicine cup, and fill it with flavored syrup. Stir until the powder is dissolved, and let your child drink it up!

Nurse Nightingale teaches Big about the different ways he might take his asthma medicines, including overviews on inhalers, nebulizers, and spacers.

Answers About Complementary and Integrative Medicine—Autism Toolkit

What is complementary and integrative medicine (CIM)?

Many families of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have questions about other types of treatments for symptoms of ASD. They may read about these online or hear about them from other parents.

Complementary medicine refers to practices that are used in addition to the educational, behavioral, and medical interventions recommended by your child’s pediatrician and schools.

Alternative medicine refers to treatments that are used in place of the recommendations of your child’s pediatrician.

When traditional and complementary practices are used together, it is often called integrative medicine.

CAM (complementary and alternative medicine) is another way of saying complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) treatments.

Pediatricians are trained to recommend evidence-based treatments. This means scientific studies have been done to see if the treatments work well and are safe. Studies are being done on CIM therapies to see if any of them work well and are safe. At this time, however, most CIM treatments are not proven to treat ASD.

Complementary and integrative medicine is often separated into the following categories:

- Biological. Examples are supplements, diets, and medicines. Some people think biologicals treat problems with the immune system, the digestive system, or the brain. These treatments are usually based on people’s theories or ideas about ASD and not scientific research studies.

- Mind-body medicine. Examples include biofeedback, auditory integration training, and optometric (eye muscle) exercises.

- Manipulation. Massage and craniosacral manipulation are 2 examples.

- Energy medicine. One example is qigong.

How do families learn about CIM and alternatives to traditional medicine and educational practices?

Most families learn about CIM online, in books, in other media, and from other families. There are still not many studies of these methods in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Peer-reviewed means that other scientists have looked at the studies and made sure they were done well.

You will want to understand the evidence for any treatment you want to try for your child. Questions you might ask include

- Has it been published in a research journal where experts have reviewed the study and the results?

- How good was the study? Did it have enough children in it to make the claims it made? Was the treatment the same for all children? Was there a placebo (substitute with no expected effect, such as a sugar pill) so that the results could be compared with results of children not receiving the treatment but receiving similar attention? Did the children get other treatment that would change the result?

- Will your insurance cover it? How much will it cost? Most health care insurers will not cover treatments that are not evidence based.

- Will my child miss or have to stop other treatments to use it?

- What are the side effects? Every intervention or treatment has some potential side effects.

How do parents decide if it’s safe to use a CIM treatment?

Many adults in the United States use CIM treatments themselves. Parents who use CIM treatments on themselves are more likely to use them with their children.

You can work with your pediatrician to look at the evidence for a treatment you are interested in and decide together if the chance of a benefit is worth any risk from the treatment.

Because there is little science to guide parents in CIM use, it is important to try any treatment step-by-step. Discuss with your pediatrician any CIM therapies you are thinking about.

Children with ASD learn skills and grow up, so over time, many children may seem to improve with or without a CIM treatment. It is important to also stop a treatment at times to see if it was helping. If it seems like it was not helping, you might want to stop it for good. If it seems like it was helping, restart the treatment and check again to see if the treatment keeps working. This can help you see if changes in your child are because of the CIM treatment or if they are because of something else. It is also important to only change one therapy at a time so that you can evaluate any results.

Are CIM methods harmful?

Some might be. For example, no one knows the long-term effects of high-dose vitamins or supplements in young children. Some vitamins may be given at doses high enough to cause side effects. Dietary restriction might also decrease needed nutrients.

Some CIM treatments, such as chelation and intravenous immunoglobulins, have known side effects and may put a child at risk. For example, chelation can cause seizures, heart arrhythmias, and kidney problems. Intravenous immunoglobulins are used to treat severe immune deficiencies but can cause allergic reactions and blood clots. Others, such as stem cell therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, have not been shown to work for ASD at this time and have risks. Stem cell therapy can cause the growth of tumors. Hyperbaric oxygen can cause the eardrums to rupture.

There are costs for CIM treatments, and each family must decide if they can afford them.

Should I tell my child’s pediatrician if I am planning to use or using a CIM therapy with my child?

Many families do not think that their child’s pediatrician needs to know about a CIM treatment because they can get it without a prescription or from a complementary provider. Families may be concerned that their child’s pediatrician may not understand the treatment or may not approve of it.

It is important to tell your child’s pediatrician about all the treatments you are using for your child. This way you can check for side effects or problems with other medications or treatments your child receives. If your child is on the gluten-free/casein-free diet, for example, your child’s pediatrician can help you see if your child is getting enough calcium and vitamin D. He may then refer your child to a registered dietitian if there are concerns. If the pediatrician explains that he does not know about a CIM treatment, you could learn about the CIM together so that you can discuss benefits and risks.

In a medical home, which is not a place but a way of working together to care for your child, families and doctors partner to plan health care. It is important for families and pediatricians to have an open conversation about CIM treatments.

Your child’s doctor may not agree that the treatment you wish to try has enough scientific evidence to support its use. But you still need to discuss it so that your child’s doctor can help you keep an eye on your child for side effects or response. You and your child’s pediatrician are partners in your child’s health care.

© 2020 American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved.

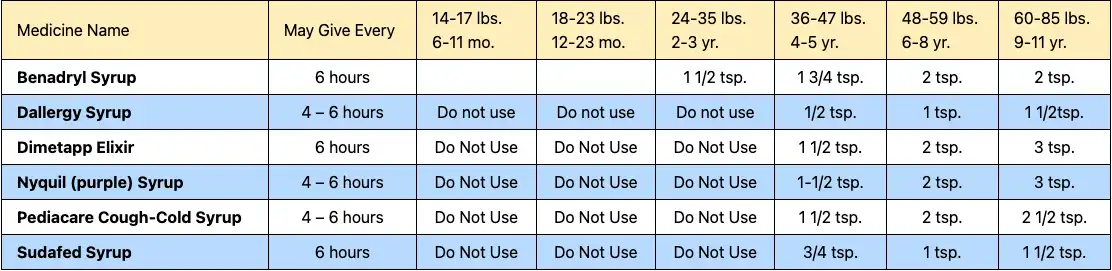

IMPORTANT! PLEASE READ: The FDA acknowledges that the ingredients in these cough and cold products have not been tested by today’s standards to identify their levels of efficacy and safety. While further studies are pending, the manufacturers are voluntarily relabeling their recommended use of these products to “Do Not Use” in children less than 4 years of age. Given the need for further research, the dosages listed below are the current recommendations of our practice.

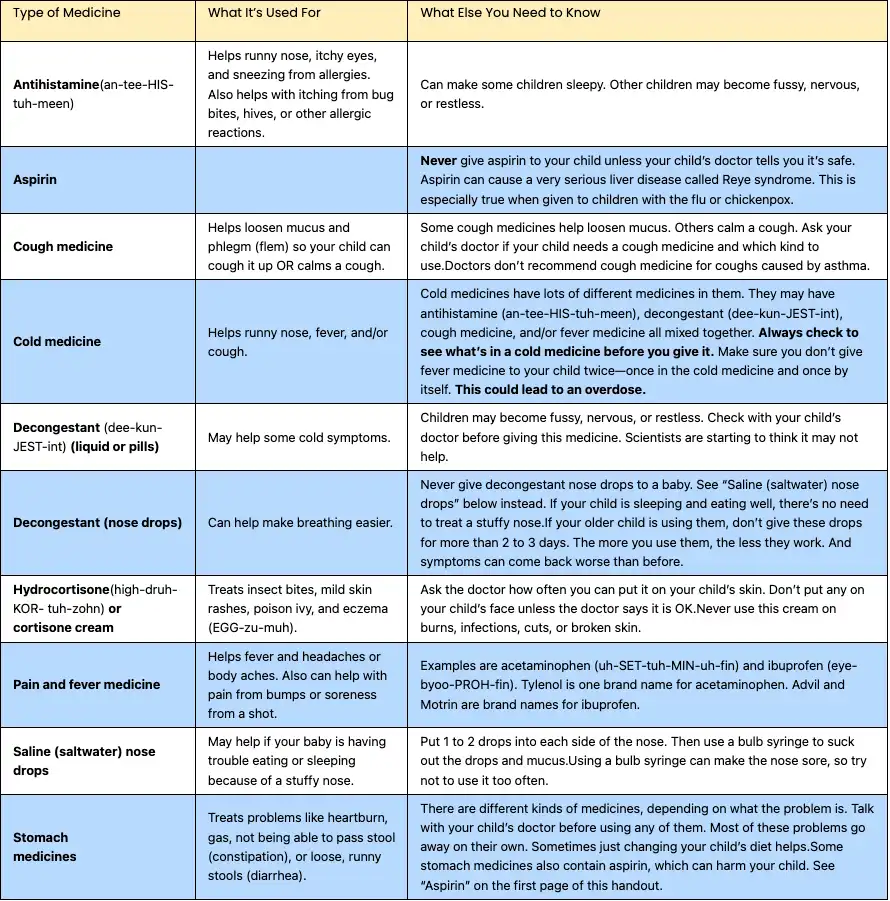

Dosages for cold medicines for different weights and ages

What Parents Need to Know

Where do you turn for help when your child gets sick? You may call your child’s doctor or another health care professional. You might call a parent or friend for advice. You may look on the Internet or in a book.

While most children in North America receive conventional medicine when they are sick, many parents also want to know about natural therapies. Alternative medicine, complementary medicine, folk medicine, holistic medicine, and integrative medicine are some terms used to describe these different therapies. Read on for more information from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) about complementary and integrative medicine.

Terms to Know

Conventional medicine, also known as Western or mainstream medicine, describes treatments or therapies used by a medical doctor (MD), doctor of osteopathy (DO), nurse practitioner (NP), or physician assistant (PA). Other conventional health care professionals include physical therapists, psychologists, dietitians, and registered nurses. Conventional therapies include, for example, antibiotics for an infection or an inhaler for asthma.

Alternative medicine describes a treatment or therapy used in place of conventional medicine. For example, butterbur can be used in place of medications to prevent migraine headaches.

Complementary medicine describes a treatment or therapy used along with conventional medicine. For example, acupuncture can be used along with medicine to treat pain.

Folk medicine describes a treatment or therapy that is passed down through generations within a culture. Most folk medicines are considered to be complementary or alternative medicine. For example, chicken soup can be used to treat a cold or the flu.

Approaches to Patient Care

Holistic medicine describes an approach to patient care that focuses on the body, mind, and spirit of the patient as well as social and environmental aspects of health.

Integrative medicine describes an approach to patient care that uses both conventional and complementary therapies that are safe and effective. Integrative clinicians promote health, focus on prevention, and encourage patients and their families to be part of the healing process.

Common Questions

Q: Are all “natural” therapies safe?

A: No. Therapies are not safe just because they are natural. Side effects from natural therapies are rare but can occur. Check with your child’s doctor before adding or changing any therapy.

Q: Does the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulate natural products?

A: Yes. The FDA regulates natural products such as dietary supplements. However, they are regulated as a food. They are not regulated like medicines. While most people can avoid buying rotten tomatoes or bruised fruit, it’s much harder to avoid poor-quality supplements. The FDA does not guarantee the purity, potency, effectiveness, or safety of natural products sold as dietary supplements.

Q: Do natural therapies really work?

A: More research is needed for all kinds of therapies for children, including natural therapies. Some natural therapies may benefit children with certain conditions but may not benefit children with other conditions. This is also true for conventional therapies.

Q: Do you need a special license to practice complementary medicine?

A: Each state has different licensing rules. Check with the licensing board for your state to find out if a health care professional has a license to practice. If your state does not require a license to practice (for example, some states do not license acupuncturists), you should check to see if the health care professional is certified by a national professional organization. Always ask about a health care professional’s training and experience. Find out if the health care professional has been specifically trained to treat children and how many children he or she treats each week.

Q: Will insurance pay for it?

A: Insurance companies and flexible health care spending accounts have many different plans that cover different therapies. There is often less coverage for complementary therapies than for conventional care. Check with your insurance company.

Q: Why is it important to talk with my child’s doctor about these treatments?

A: Talking with your child’s doctor helps you know if a treatment is safe and effective. Talk about all products you are giving to your child, including vitamins, herbs, and other supplements. This is especially important because there can be dangerous side effects when some medicines or therapies are given with other medicines and therapies at the same time. Bring all the products you give your child to each medical appointment. Always let your doctor know if another health care professional is caring for your child so that care can be coordinated.

Ask all your child’s health care professionals to talk with each other. Open communication is the best way to promote the safest care possible.

Q: Are there pediatricians who practice integrative medicine?

A: Yes. More and more pediatricians are offering complementary therapies and advice as part of their medical practice. Although pediatricians recommend conventional therapies such as vaccines to protect children from illness, many pediatricians also recommend and refer patients for complementary therapies such as herbs, dietary supplements, special diets, and exercise. There are pediatricians who have completed integrative medicine training. Many have completed a fellowship in integrative medicine, and many have completed certification through the American Board of Integrative Holistic Medicine or the American Board of Integrative Medicine. There are lists available of board-certified physicians. Also, a pediatrician’s Web site may provide information about professional training or fellowship completion.

Q: Does the AAP have members who work with complementary and integrative medicine?

A: Yes! The AAP has a Section on Integrative Medicine, which includes more than 425 pediatricians across the United States and Canada. You can find out more about this section at https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Sections/Section-on-Integrative-Medicine/Pages/SOIM.aspx.

Resources

Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health

MedlinePlus from the National Institutes of Health, US National Library of Medicine

This site includes information on dietary supplements as well as medications and common medical conditions.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health from the US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health

Physicians Board Certified by the American Board of Integrative Medicine

www.aihm.org/search/custom.asp?id=4620

Remember

Talk with your child’s doctor about all treatments your child is receiving. This includes prescribed medications, home remedies, over-the-counter remedies, and dietary supplements such as vitamins or herbs. Also, tell your child’s doctor if your child is seeing any other complementary or mainstream health care professionals. Your child’s health and well-being depend on open communication, trust, and respect among all health care professionals.

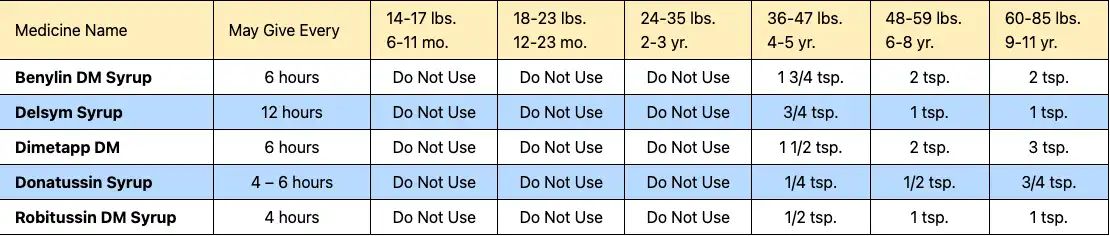

IMPORTANT! PLEASE READ: The FDA acknowledges that the ingredients in these cough and cold products have not been tested by today’s standards to identify their levels of efficacy and safety. While further studies are pending, the manufacturers are voluntarily relabeling their recommended use of these products to “Do Not Use” in children less than 4 years of age. Given the need for further research, the dosages listed below are the current recommendations of our practice.

Dosages for cough medicines in various weights and ages

Giving Eye drops to your Toddler

Administering eye drops can be uncomfortable to a toddler. Have your child lie on his back and shut his eyes as tight as he can. Place one to two drops in the inner corner of each eye. Tell him to relax his eyes. The liquid will seep into the eye without tears or fuss! Wipe off the excess with a clean cloth or tissue.

Important Safety Information

Giving medicine in the right way can help your child feel better and get well faster. However, any kind of medicine can cause harm to a child if given the wrong way.

What You Need to Know

There are 2 main types of medicine: over-the-counter and prescription medicine. Medicine that a doctor orders from a pharmacy is called prescription medicine. Over-the-counter (sometimes called OTC) medicine can be bought without a doctor’s prescription. This doesn’t mean that OTC medicines are harmless. Like prescription medicine, OTC medicines can be dangerous if not taken the right way.

Read on for more information from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) about giving medicines safely to children and what to do if you think your child has swallowed any medicine or substance that might be harmful.

Here are 4 important steps to follow when giving your child medicine.

Keep Medicines Up and Away

Read and Follow the Label Directions

Give Medicine Only as Recommended

Always Measure Liquid Medicines With the Right Dosing Tool

1. Keep Medicines Up and Away

Children are curious and like to explore. Here are ways to help keep them from getting into medicines.

Keep medicines up high, out of reach, and out of sight. This includes medicine that is in the refrigerator. If possible, keep medicines in a locked cabinet or box or other container.

Keep medicines in the bottle they came in with the safety caps on tight. Keep in mind that safety caps make it harder for children to get into the medicine, but they do not stop children from getting in the medicine all the time.

Get rid of old medicines and medicines that you are not using. Look at the medicine box or bottle for the date after which the medicine should not be used (expiration date). Medicines that are used after that date can be harmful or may not work well. Learn how to throw out medicines safely by calling 1-800-222-1222 (Poison Help), or check the US Food and Drug Administration Web site at www.fda.gov for information.

2. Read and Follow the Label Directions

Before you give your child any medicines, be sure you know how to use them. Check the label every time you give medicine to your child. If you need to give medicine at night, turn on the light to make sure you are giving the right medicine. If you have any questions about the medicine, ask your child’s doctor, health care professional, or pharmacist.

For Over-the-counter Medicines

Check the box or bottle. Make sure it only treats the symptoms your child has.

Check the ingredients. Are the main ingredients (“active ingredients”) of the medicine you are giving the same as the ingredients in other medicines your child is taking? It’s important that you don’t give your child too much of the same medicine. For example, acetaminophen is an ingredient in many OTC and prescription medicines, such as medicines for pain or fever and cough/cold medicines.

Check what age the medicine is for. You may need to contact your child’s doctor first for certain ages, such as if your child is younger than 2 years.

Check the facts. Read the side of the medicine box or bottle (the part called “Drug Facts”) and check the “Warnings” section.

Check the chart. Check the chart on the label to see how much medicine to give. If you know your child’s weight, use that to help you see how much medicine to give. If not, use your child’s age.

For Prescription Medicines

Be sure you understand how much, how often, and how long your child needs the medicine. If you have any questions, ask your child’s doctor or pharmacist. For example, you may ask, “The instructions say to give the medicine 4 times a day. Does that mean every 6 hours? If yes, do I need to wake up my child in the middle of the night?” or “My child feels much better. Can I stop giving the medicine?”

3. Give Medicine Only as Recommended

Cough and Cold Medicines

The AAP does not recommend OTC cough and cold medicines for children younger than 4 years. Children 4 to 6 years of age should only use OTC cough and cold medicines if a doctor says it is OK. After age 6 years the directions on the package can be followed (but be very careful with dosing).

Fever and Pain Medicines

Acetaminophen and ibuprofen can help your child feel better if your child has a headache or body aches or a fever. They can also help with pain from injuries such as a bruise or sprain and from soreness caused by a needle shot.

Acetaminophen for children comes in liquid as well as pills that can be chewed. It also comes as a pill that is put in the rectum (suppository) if your child is vomiting and can’t keep down medicine taken by mouth.

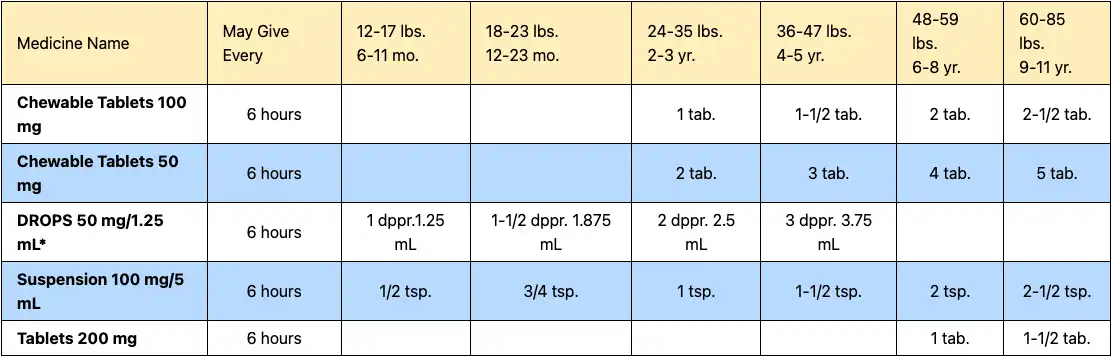

Ibuprofen comes in liquid for infants and children and chewable tablets for older children. With ibuprofen, keep in mind that there are 2 different kinds of liquid medicines—one for infants and one for children (including toddlers and children up to age 11 years). Infant drops are stronger (more concentrated) than the medicine for children.

NOTE: Always look carefully at the label on the medicine and follow the directions. Each type of medicine has different directions based on the age and weight of a child. You may need to ask your child’s doctor about the right dose for your child. For example, you will need to ask how much acetaminophen is the right dose for a child younger than 2 years.

4. Always Measure Liquid Medicines With the Right Dosing Tool

Liquid medicines must be measured carefully. Always use the dosing tool that comes with the medicine or that your child’s doctor or pharmacist tells you to use. Never use teaspoons, tablespoons, or other household spoons to measure medicine.

Four types of dosing tools are available: droppers (for infants), syringes, dosing spoons, and medicine cups. The units of measure on a dosing tool may be marked “tsp,” “tbsp,” or “mL.” One tsp (teaspoon) is equal to 5 mL (milliliters), and one tbsp (tablespoon) is equal to 15 mL (milliliters). To measure the right amount, make sure the number and unit for the dose of your child’s medicine matches the number and unit on your dosing tool.

Types of Dosing Tools

Dropper. A dropperful is the same as 0.8 mL.

Syringe. 1 tsp is the same as 5 mL.

Dosing spoon. 1 tsp is the same as 5 mL.

Medicine cup. 1 tbsp is the same as 15 mL.

What to Do for Poisoning

Sometimes parents find their child with something in his or her mouth or with an open bottle of medicine. If you think your child has swallowed any medicine or substance that might be harmful, stay calm and act fast.

Call 911 or your local emergency number right away if you cannot wake up your child (the child is unconscious), your child is not breathing, or your child is shaking (having convulsions or seizures).

Call 1-800-222-1222 (Poison Help) if your child is breathing and awake (conscious). A poison expert in your area is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. You will be told what to do for your child and whether you can watch your child at home or need to go to the hospital.

NOTE: You should not make a child throw up.

Dosages for ibuprofen medicines for various weights and ages

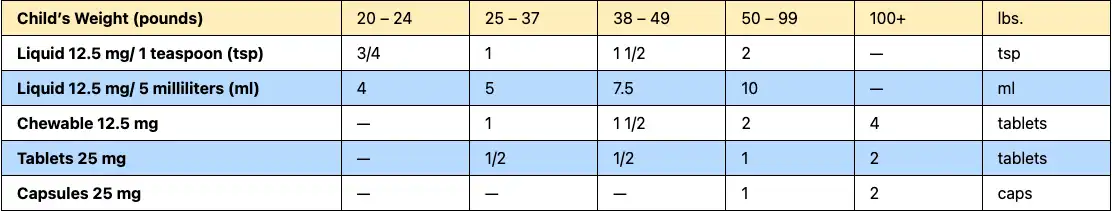

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) Dose Table for every 6 – 8 hours

When to Use. Treatment of allergic reactions, nasal allergies, hives and itching.

Table Notes:

- AGE LIMITS. For allergies, don’t use under 1 year of age. (Reason: it causes most babies to be sleepy). For colds, not advised at any age. (Reason: no proven benefits). They should be not be given if under 4 years old. If under 6 years, don’t give products with more than one ingredient in them. (Reason: FDA recommendations 10/2008).

- DOSE. Find the child’s weight in the top row of the dose table. Look below the correct weight for the dose based on the product you have.

- MEASURE the DOSE. Syringes and droppers are more accurate than teaspoons. If possible, use the syringe or dropper that comes with the medicine. If not, you can get a med syringe at drug stores. If you use a teaspoon, it should be a measuring spoon. (Reason: regular spoons are not reliable.) Keep in mind 1 level teaspoon equals 5 ml and that ½ teaspoon equals 2.5 ml.

- ADULT DOSE. 50 mg

- HOW OFTEN. Repeat every 6 hours as needed.

- CHILDREN’S BENADRYL FASTMELTS. Each fastmelt tablet equals 12.5 mg. They are dosed the same as chewable tablets.

Using Liquid Medicines

Many children’s medicines come in liquid form. Liquid medicines are easier to swallow than pills. But they must be used the right way.

Types of Liquid Medicines

There are 2 types of liquid medicines:

Medicines you can buy without a doctor’s prescription (called over-the-counter or OTC)

Medicines a doctor prescribes

OTC Medicines

All OTC medicines have the same kind of label. The label gives important information about the medicine. It says what it is for, how to use it, what is in it, and what to watch out for. Look on the box or bottle, where it says “Drug Facts.”

Check the chart on the label to see how much medicine to give. If you know your child’s weight, use that first. If not, go by age. Check the label to make sure it is safe for infants and toddlers younger than 6 years. If you are not sure, ask your child’s doctor.

Prescription Liquid Medicines

Your child’s doctor may prescribe a liquid medicine. These medicines will have a different label than OTC medicines. Always read the label before you give the medicine to your child. It is also important to always use the dosing device that comes with the medicine or that your doctor or pharmacist tells you to use.

With OTC or prescription medicines, be sure to call your child’s doctor or pharmacist* if you have any questions about:

How much medicine to give.

How often to give it.

How long to give it.

A Word About Infant Drops

Infant drops are stronger than syrup for toddlers. Parents may make the mistake of giving higher doses of infant drops to a toddler, thinking the drops are not as strong. Be sure the medicine you give your child is right for his or her weight and age.

How to Give Liquid Medicines

Follow the directions exactly. Some parents give their children too much medicine. This will not help them get better faster. And it can be very dangerous, especially if you give too much for several days. Always read the label carefully.

How to Measure Liquid Medicines

Use the dropper, syringe (sir-INJ), medicine cup, or dosing spoon that comes with the medicine. If the medicine does not come with a dosing device, ask your doctor or pharmacist for one that should be used. Never use teaspoons, tablespoons, or other household spoons to measure medicine.

Medicine can be measured in different ways. You may see teaspoon (tsp), tablespoon (tbsp or TBSP), or milliliters (mL, ml, or mLs) on the dosing device.

Tips

1 teaspoon (tsp) = 5 milliliters (mL)

3 teaspoons (tsp) = 1 tablespoon (tbsp)

1 tablespoon (tbsp) = 15 milliliters (mL)

Medicine Cups

1 tbsp is the same as 15 mL.

Be sure to use the cup that comes with the medicine. These often come over the lids of liquid cold and flu medicines. Don’t mix and match cups to different products. You might end up giving the wrong amount.

Don’t just fill it up. Look carefully at the lines and letters on the cup. Use the numbers to fill the cup to the right line. Ask your pharmacist to mark the right line for your child if you are not sure. Be sure the cup is level. You can check by putting it on a flat surface.

Dosing Spoons

Fill the dosing spoon while holding it upright.

These work well for older children who can “drink” from the spoon. Use only the spoon that comes with the medicine. Be sure to use the lines and numbers to get the right amount for your child. Or ask your pharmacist to mark the right line if you are not sure.

Droppers or Syringes

In this example, a dropperful is the same as 0.8 mL.

Don’t just fill the dropper or syringe to the top. Read the directions carefully to see how much to give your child. Look at the numbers on the side of the dropper or syringe. Use the numbers to fill it to the right line. Or ask your pharmacist to mark the right line if you are not sure. (If the syringe has a cap, throw it away before you use it. The cap could choke your child.)

1 tsp is the same as 5 mL.

Don’t put the medicine in the back of the throat. This could choke your child. Instead, squirt it gently between your child’s tongue and the side of the mouth. This makes it easier to swallow.

How to Make Sense of the Messages

Your child is sick or hurt and the first thought on your mind is, “How can I make my child better?” That’s natural. No parent wants his or her child to suffer. So how do you decide what medicines to give or treatments to try?

Aside from your pediatrician, what sources can you trust? Commercials and magazine ads claim products help and heal. Web sites claim to have “cutting-edge” health information. TV programs and newspapers report on the “latest” studies showing which treatments work and don’t work.

One challenge of parenting is sorting through all available information about children’s health. Some sources can be trusted, while others should be questioned. Read more to learn about the language of advertisers, good science, questioning your sources, using the Internet, Web site addresses, and evaluating new treatments or medicines.

The language of advertisers

Advertisers try many ways to get you to buy the products they are selling. They may use certain words or phrases to interest you, such as

“#1 Pediatrician Recommended” or “Doctor Recommended”

These are marketing terms that try to get you to buy a product. Although the product may be recommended by a group of doctors, what the advertisers don’t tell you is how many doctors or how long ago the recommendation was made. It could be 5 or 100 doctors surveyed 10 years ago.

“Patented Design”

A patent means that the maker or inventor of a product has proven to the government that he or she was the first to create the product. In return, the government gives a patent and says that only the patent holder can make or sell the product for a certain period. A patent doesn’t necessarily mean that the product is the best, is safe, or will work.

“Clinically Shown”

This phrase means that the product was tested on patients as part of a study to see if the product worked. There are many ways to conduct studies. However, if the people doing the study don’t follow strict scientific rules for doing research, the study results may have little meaning.

Good science

Scientific studies require careful planning. Researchers need to follow specific procedures and processes. Studies must follow certain rules to be considered scientifically credible, including the following:

The testing must take place in carefully controlled conditions. Researchers have to make sure to control factors that could affect the results. For example, if researchers want to know how a medicine affects a child, they have to make sure the child isn’t taking any other medicines at the same time.

Researchers need to determine how many people should be included in the study. Study size varies according to the kind of study and number of people needed to demonstrate an effect.

The group of people receiving treatment should be compared to a control group to truly test if the treatment has any effect. A control group doesn’t receive the new treatment, but instead may be given a placebo (sugar pill) or an alternative treatment.

Good clinical studies should be replicated. That means other researchers should be able to do the same study again using different subjects and get similar results. We know we can trust the findings when different studies come to the same conclusions.

Well-done, scientifically sound studies should go through peer review. This means other experts on the topic being studied should review each study and make sure that all proper scientific standards were met.

Questioning your sources

It’s important to ask the following questions when evaluating a source:

1. What is the source?

In general, sources you can trust include accredited medical schools, government agencies, professional medical associations, and recognized national disorder/disease-specific organizations. However, don’t rely mainly on the name of the organization—do your own research.

2. Who is the expert?

The doctors or researchers being interviewed may sound like experts, but what are their credentials? What expertise and experience do they have? They may be doctors, but are they experts on the particular issue being talked about? Are there conflicts of interest? Are they working for a company that may benefit from their “expert” support? Are they being paid for their support of a product? If so, this could influence what information these experts choose to share.

3. What are the facts?

Know the difference between preliminary and confirmed findings—a “breakthrough” finding may seem promising but still has to be replicated and reviewed over time. Don’t let a headline make you think that “new study” is the same as “proven.” Another word of caution: “new” doesn’t mean improved. Sometimes newer medicines are not an improvement over older medicines and cost much more.

Using the Internet

The Internet can be a valuable source of medical information and advice, but you can’t trust everything you read. The Internet also is the source of a lot of health-related theories and opinions that haven’t been proven.

Begin your search for information with the most reliable, general-information Web sites and expand from there. The Web site for the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), http://www.aap.org, is a good starting point.

Web site addresses

The last 3 letters in a Web site address can tell you what type of organization or company set up the site.

.gov— Government Web sites often provide large amounts of information for the general public.

.org— Nonprofit organization Web sites may contain useful information. However, not all organizations put out reliable materials. Search for information on nonprofit Web sites that you have heard of and have good reputations.

.edu— Academic or education-based Web sites may have educational materials for parents.

.com— Commercial Web sites often are designed to sell you something. They are not necessarily a source of reliable information.

Evaluating new treatments or medicines

When you come across a new treatment or medicine, ask yourself the following questions:

1. Will it work for my child?

Be suspicious if the information describing the treatment or medicine

Claims it will work for everyone.

Uses a story about one person’s experience or testimonials as proof that it works.

Cites only one study as proof.

Cites a study without a control (comparison) group.

2. How safe is it?

Be suspicious if the treatment or medicine

Comes without directions for proper use.

Doesn’t list contents or ingredients.

Has no information or warnings about side effects.

Is described as “harmless” or “natural.” Remember, most medication is made from natural sources. A “natural” treatment doesn’t necessarily work and, worse yet, actually may be harmful to your child. Being “natural” does not necessarily mean it is good or safe.

Isn’t approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Appears on an infomercial.

3. How is it promoted?

Be suspicious if the ad for the treatment or medicine

Claims it’s based on a secret formula.

Claims it works immediately and permanently.

Claims it’s a “miraculous” or an “amazing” breakthrough.

Claims it is a “cure.”

Indicates it’s available from only one source.

Remember

You shouldn’t trust everything that you read or hear. Make sure that your pediatrician knows about your questions and concerns; share the information you’ve found. You and your pediatrician are partners in your child’s health.

Choosing Over-The-Counter Medicines For Your Child

“Over-the-counter” (OTC) means you can buy the medicine without a doctor’s prescription. Talk with your child’s doctor or pharmacist* before giving your child any medicine, especially the first time.

All OTC medicines have the same kind of label. The label gives important information about the medicine. It says what it is for, how to use it, what is in it, and what to watch out for. Look on the box or bottle, where it says “Drug Facts.”

Check the chart on the label to see how much medicine to give. If you know your child’s weight, use that first. If not, go by age. Check the label to make sure it is safe for infants and toddlers younger than 2 years. If you are not sure, ask your child’s doctor.

Call the Doctor Right Away If…

…your child throws up a lot or gets a rash after taking any medicine. Even if a medicine is safe, your child may be allergic* to it.

Your child may or may not have side effects* with any drug. Be sure to tell the doctor if your child has any side effects with a medicine.

Over-the-Counter Medicines

There are 2 types of medicines you can buy:

1) over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and

2) prescription medicines. OTC medicines are those you can buy without a doctor’s order. Prescription medicines are those you can only buy with a doctor’s order (a prescription). This handout is about prescription medicines.

Ask the Doctor or Pharmacist

Many parents have questions about their children’s prescription medicines. Labels can be hard to read and understand. But it’s important to give medicines the right way for your child’s health and safety.

Before you give your child any medicine, be sure you know how to use them. Here are some questions you can ask the doctor or pharmacist*:

How will this medicine help my child?

How much medicine do I give my child? When? For how long?

Should my child take this medicine with food or on an empty stomach?

Are there any side effects* from this medicine?

How can I learn more about this medicine?

When will the medicine begin to work?

What should I do if my child misses a dose?

What if my child spits it out?

Can this prescription be refilled? If so, how many times?

Also, always tell your child’s doctor:

If your child is taking any other medicines (even OTC medicines) and

If your child has any reactions to the medicines.

Call the Doctor Right Away If…

…your child throws up a lot or gets a rash after taking any medicine. Even if a medicine is safe for other children, your child may be allergic* to it.

Your child may or may not have side effects with any drug. Be sure to tell the doctor if your child has any side effects with a medicine.

Read the Label

Here is what the parts of a prescription label mean. (See example on second page of this handout.)

Prescription number. Your pharmacy will ask for this number when you call for a refill.

Your child’s name.

Name of the medicine. Make sure this matches what your child’s doctor told you. The strength of the medicine may also be listed (for example, 10 mg tablets).

QTY. “Quantity” or how much is in the package.

Expiration date (Mfr Exp). The medicine in this package will only work until this date. Throw away any medicine left after this date.

f.Directions. This tells you how your child needs to take the medicine and what it is for. The label should match what your child’s doctor told you.

Here are some examples:

“Take 4 times a day.” Give the medicine to your child 4 times during the day. For example, at breakfast, lunch, dinner, and before bed.

“Take every 4 hours.” Give the medicine to your child every 4 hours. This adds up to 6 times in a 24-hour period. For example, 6:00 am, 10:00 am, 2:00 pm, 6:00 pm, 10:00 pm, and 2:00 am. Most medicines don’t have to be given at the exact time to work, but some do.

“Take as needed as symptoms persist.” Give the medicine to your child only when needed.

“Take with food.” Give the medicine to your child after a meal. This is for medicines that work better when the stomach is full.

g.Refills. The label will show the number of refills you can get. “No refills—Dr. authorization required” or “0” means you need to call your child’s doctor if you need more. The doctor may want to check your child before ordering more medicine.

h.Date prescription was filled.

i.Doctor’s name.

j. Pharmacy’s name, address.

k. Special messages. The medicine may have extra bright-colored labels with special messages. For example, you may see, “Keep refrigerated,” “Shake well before using,” or “May cause drowsiness.” Be sure to ask if you don’t understand what they mean.

Tips

Use safety caps. Always use child-resistant caps.

Store medicines in a locked, childproof cupboard if you have children at home.

Store medicines in a cool, dry place. Wetness can hurt medicines. So don’t store them in a bathroom. Some medicines need to be kept in a refrigerator.

Never let your child take medicine alone. Don’t call medicine “candy.” (If you do, your child may try to eat some when you’re not around.)

Watch your child carefully. Children can find medicine where you least expect it. Your child might find it in a visitor’s purse or at other people’s homes. On moving day, medicines and poisons may be out where children can find them.

Use of Medicines in Sports (Care of the Young Athlete)

The primary use of medicines in sports is to treat pain and inflammation. Athletes may also take medicines to treat specific medical conditions, such as asthma or diabetes, or to treat common illnesses, like colds, congestion, cough, allergies, diarrhea, and skin infections.

Athletes should talk with their doctor before using any medicines to learn how to use them correctly, how much to take, if there are any side effects, and how they might affect their sports. The use of supplements, including iron and vitamins, as well as any supplement used to enhance sports performance, should also be discussed with a doctor.

General guidance

Medicines should only be a small part of an overall treatment plan. Sports injuries need to be properly diagnosed and treated in a way that looks at both the causes and effects of the injury.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are helpful for chronic conditions in which the inflammation does not help the injury heal. For acute injuries, they may actually delay healing.

Do not use more than one NSAID at the same time. It is fine to use with acetaminophen. NSAIDs should be taken with food, even if it is just a snack.

Pain medicines can be used to treat acute injuries. However, in some cases, pain relief can mask important warning signs and lead to further injury.

Long-term use of medicines that reduce pain or inflammation should not occur without the approval of a doctor. If long-term use is needed, athletes should see their doctor regularly to check for side effects.

All medicines can have side effects and can affect training and sports performance. Athletes should always check with a doctor before using medicines to treat injuries or illnesses.

Always follow the instructions for dosing on the package or from your doctor when using medicines.

Never borrow or share prescription medicines—even if they are used for a similar condition.

Supplements are medicines, even though they are not packaged or advertised as such, and should be treated with the same caution.

Athletes who may be drug tested should be aware that many prescription and nonprescription medicines are banned from use in training and competition. A list of banned substances can be found at www.usada.org.

Nonprescription medicines

Nonprescription medicines are ones that do not require a doctor’s order. However, this does not mean they are safer than prescription medicines. Two of the most common nonprescription medicines used in sports are

NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen (2 brand names are Advil and Motrin) and naproxen (one brand name is Aleve), to reduce pain and inflammation (swelling)

Analgesic medicine, such as acetaminophen (one brand name is Tylenol), to reduce pain

These medicines are most often used to relieve pain, spasm, or chronic inflammation. For acute injuries such as sprains, strains, and fractures, long-term (more than 3 to 7 days) use of NSAIDs may actually delay healing. Short courses (less than 3 to 7 days) of these medicines may speed recovery in ligament injuries, while their effects on muscular and bony injuries are less clear. However, with overuse injuries, such as tendonitis, bursitis, shin splints, or arthritis, they may help the recovery process. Acetaminophen can be used to reduce pain in both acute and overuse injuries but is not helpful in reducing swelling or inflammation.

Side effects of NSAIDs

NSAIDs, both prescription and nonprescription, have side effects including stomach upset, gastritis, and ulcers. They also have a blood-thinning effect and can increase the likelihood of bleeding after a cut, deep bruise, muscle strain, or head injury. Long-term use can affect the kidney and liver. Athletes who are dehydrated or have kidney or liver disease should not take NSAIDs.

When to see a doctor

Medicines alone are rarely sufficient to treat sports injuries. Pain and swelling can also be treated with rest, ice, immobilization, compression, bracing, and elevation. Medicines can mask pain, which can lead to further injury. For more severe or ongoing problems, athletes should talk to their doctor about further diagnostic testing and additional treatment options. In general, if athletes need to take a medicine to play, they should see a doctor.

Listing of resources does not imply an endorsement by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The AAP is not responsible for the content of the resources mentioned in this publication. Web site addresses are as current as possible, but may change at any time. Products are mentioned for informational purposes only and do not imply an endorsement by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Using Over-the-Counter Medicines with Your Child

“Over-the-counter” (OTC) means you can buy the medicine without a doctor’s prescription. This doesn’t mean that OTCs are harmless. Like prescription medicines, OTCs can be dangerous if not taken the right way. Talk with your child’s doctor before giving your child any medicine, especially the first time.

All OTC medicines have the same kind of label. The label gives important information about the medicine. It says what it is for, how to use it, what is in it, and what to watch out for. Look on the box or bottle, where it says “Drug Facts.”

Ask the Doctor or Pharmacist

Check the chart on the label to see how much medicine to give. If you know your child’s weight, use that first. If not, go by age. Check the label to make sure it is safe for infants and toddlers younger than 2 years. If you are not sure, ask your child’s doctor.

Before you give your child any medicines, be sure you know how to use them. Here are some questions you can ask the doctor or pharmacist*:

How will this medicine help my child?

Can you show me how to use this medicine?

How much medicine do I give my child? When? For how long?

Are there any side effects* from this medicine?

How can I learn more about this medicine?

What if my child spits it out?

Does it come in chewable tablets* or liquid?

Also, always tell your child’s doctor or pharmacist:

If your child is taking any other medicines.

If your child has any reactions to a medicine.

Call the Doctor Right Away If…

…your child throws up a lot or gets a rash after taking any medicine. Even if a medicine is safe, your child may be allergic* to it.

Your child may or may not have side effects with any drug. Be sure to tell the doctor if your child has any side effects with a medicine.

About Pain and Fever Medicines

Acetaminophen (uh-SET-tuh-MIN-uh-fin) and ibuprofen (eye-byoo-PROH-fin) help with fever and headaches or body aches. Tylenol is one brand name for acetaminophen. Advil and Motrin are brand names for ibuprofen.

These medicines also can help with pain from bumps, or soreness from a shot. Ask the doctor which one is best for your child.

What Else You Need to Know

Never give ibuprofen to a baby younger than 6 months.

If your child has a kidney disease, asthma, an ulcer, or another chronic (long-term) illness, ask the doctor before giving ibuprofen.

Don’t give acetaminophen or ibuprofen at the same time as other OTC medicines, unless your child’s doctor says it’s OK.

A Warning About Aspirin

Never give aspirin to your child unless your child’s doctor tells you it’s safe. Aspirin can cause a very serious liver disease called Reye syndrome. This is especially true when given to children with the flu or chickenpox.

Ask your pharmacist about other medicines that may contain aspirin. Or, contact the National Reye’s Syndrome Foundation at 1-800-233-7393 or www.reyessyndrome.org.

What to Do for Poisoning:

Call the Poison Center if you’re not sure.

Sometimes parents find their child with something in his or her mouth or with an open bottle of medicine. The Poison Center can help you find out if this could hurt your child. Don’t wait until your child is sick to call the Poison Center.

Call 911 or your local emergency number right away!

if your child:

Is passed out and can’t wake up, OR

Is having a lot of trouble breathing, OR

Is twitching or shaking out of control, OR

Is acting very strange.

Don’t use syrup of ipecac.

If you have syrup of ipecac in your home, flush it down the toilet and throw away the bottle. Years ago people used syrup of ipecac to make children throw up if they swallowed poison. Now we know that you should not make a child throw up.

Certified by the American Board of Pediatrics

Partnering with You on Your Child's Health Journey